T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

Some biographical Notes:

- Harvard education- wealthy family from New England- born in St. Louis Missouri

- Wrote dissertation but did not defend it- a critique of the psychology of consciousness

- Held job at Lloyd’s bank in London

- Was an Anglican

- Ex-patriot- gave up his “American-ness”

- Met Ezra Pound in Paris

- Unhappy marriage to Vivien Haigh-Wood- didn’t believe in divorce- she died in 1947 and he remarried Valerie Fletcher in 1957

- He died of emphysema- was a heavy smoker

- Had a mental breakdown (had several) – went to rest house in Switzerland in 1921 and finished the Waste Land there (which he started in 1919)

- Two major stylistic methods- (1) Robert Browning- look at one character and exploring his or her twisted psyche; (2) more classical dramatic style ala Dante and Shakespeare

- Heavily influenced by Dante and French Symbolist Poets (i.e. Baudelaire)

Discussion Questions for T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”

We will be covering “The Waste Land” during our discussion this upcoming week. You will find questions below that may assist you in navigating through some of the poem’s complexities. We will attempt to cover many of these questions during section. Feel free to bring in responses you may have to any of these questions (or to other issues you locate in the text).

Some Waste Land Reminders: This is one of the most important poems of the 20th century. We will speak of it EXTENSIVELY in discussion! It is also one of the most difficult poems. Please keep certain things in mind while you are reading it: (1) pay close attention to the first line, “April is the cruellest month”- April is often the least cruel month, why is he beginning the poem in such a way. (2) when reading this poem we must be hyper-aware of its historical backdrop- WWI– Eliot published the poem in 1922, but it was written both during WWI and during its traumatic aftermath. (3) look at each section carefully and think about the titles of each section- what do the titles suggest? (4) this is an antipastoral poem, compare it to the “Spring and All” by Williams we read last week… how do they compare? (5) think about the interactions between men and women that Eliot depicts and try to reflect a little on how those interactions are played out (especially seen in “The Game of Chess”), (6) think about how this poem is both similar to and different from Pound’s Cantos… what does Eliot adopt from Pound and what does he abandon? (6) This poem is FILLED with allusions… what do these allusions do for your reading process? How do they serve as a supplementary text and why do you think Eliot used so many of them?

- A. The Burial of the Dead

(1) How does the section The Burial of the Dead actually exhibit life?

(2) How are the city and its inhabitants portrayed? Remeber the city in modernist writing is extremely important, taking on a life of its own….

(3) Excerpt to consider—Lines 60-76:

Unreal City, 60

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet. 65

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

You who were with me in the ships at Mylae! 70

That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

O keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again! 75

You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

B. A Game of Chess

1. What is the symbolic value of chess in this poem?

2. Are the woman in the chair (line 76) and the woman named Lil (line 139) the same character? What is the significance of the two dialogues in this section?

3. Excerpts to consider—Lines 111-136 & Lines 145-155:

“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

I think we are in rats’ alley 115

Where the dead men lost their bones.

“What is that noise?”

The wind under the door.

“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?”

Nothing again nothing. 120

“Do

“’You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

Nothing?”

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes. 125

“’Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?”

But

O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—

It’s so elegant

So intelligent 130

“’What shall I do now? What shall I do?”

“’I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street

‘With my hair down, so. What shall we do tomorrow?

‘What shall we ever do?”

***

You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set, 145

He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said. 150

Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling. 155

C. The Fire Sermon

1. What traces of war and destruction do you find in section 3?

2. What function does Tiresias, the blind prophet of dual gender, serve in the poem (line 218)?

3. Excerpt to consider—Lines 218-230 :

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives 220

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays, 225

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

I too awaited the expected guest. 230

D. Death by Water

1. Why does Eliot transition from fire to water?

2. What does the narrator warn the reader against?

3. Excerpt to consider—Lines 319-321:

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward, 320

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

E. What the Thunder Said

1. Does Eliot leave room for hope by the end of the poem? If so, what lines depict that?

2. Excerpt to consider—Lines 412-418:

Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison415

Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

D A

Excerpts extracted from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” in the 8th edition of The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Twentieth Century and After

Read Full Post »

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

champ’s work had a great influence on his poetry. Check this out if you want to see some of Duchamp’s pieces:

champ’s work had a great influence on his poetry. Check this out if you want to see some of Duchamp’s pieces:  by the artist and is waiting to dry. The word glazed reinforces the image of “rain water,” and thus the word itself becomes an image. Each word in this poem serves as its own image, and as the words compile together, a linguistic collage develops…

by the artist and is waiting to dry. The word glazed reinforces the image of “rain water,” and thus the word itself becomes an image. Each word in this poem serves as its own image, and as the words compile together, a linguistic collage develops… Some things to keep in mind about Stein and The Making of Americans:

Some things to keep in mind about Stein and The Making of Americans:

Let us turn to Canto 1…

Let us turn to Canto 1…

ound uses this syntax throughout his poetry in order to force his readers to make active connections between seemingly disconnected poetic fragments.

ound uses this syntax throughout his poetry in order to force his readers to make active connections between seemingly disconnected poetic fragments.

“In a Station of the Metro” (1916) is a perfect example of the Imagist construction. In 14 words, the poet is able to create and maintain an image. Much like a Cubist painting, this poem serves to FUSE together two images: the “faces in the crowd” and the “petals on a wet, black bough.” Like Cubism, Imagism fuses together images using language instead of color. The poem contains no verb, no action, it is simply an impression which is transmitted from the poet’s imagination to the page.

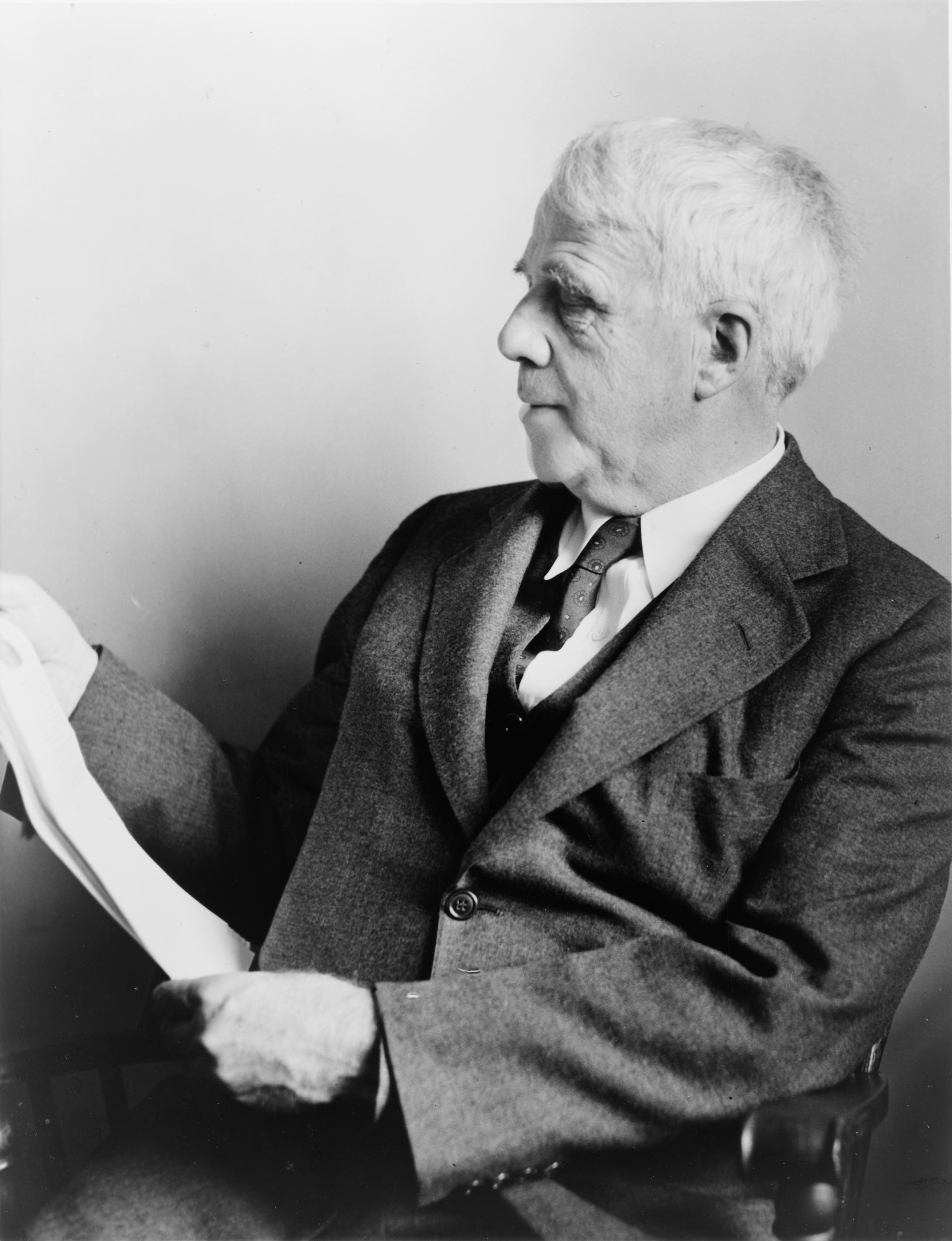

“In a Station of the Metro” (1916) is a perfect example of the Imagist construction. In 14 words, the poet is able to create and maintain an image. Much like a Cubist painting, this poem serves to FUSE together two images: the “faces in the crowd” and the “petals on a wet, black bough.” Like Cubism, Imagism fuses together images using language instead of color. The poem contains no verb, no action, it is simply an impression which is transmitted from the poet’s imagination to the page. Some notes on theme and style: Frost often uses complex philosophical themes through his poetry. The three poem we read for the class are incredibly short, yet each line contains larger philosophic and social claims. Prof. Huang spent some time going over “The Road Not Taken,” reminding us that the poem is a lament for what could have been. Frost generally resorts to natural themes, moving from the city to the forest. Frost is writing during the early decades of the 20th century, a century marked by capitalism’s modernizing forces. Film was developing, photography and photo journalism were established as means of media communication, WWI (1914-1918) and WWII (1939-1945) ravished the global economy and mindset. Frost is writing in the midst of chaos and progress, trying to create a sense balance through poetry, a “momentary stay against confusion.” The poet is the one who is able to make life stop for a moment, a simple moment in which the reader can reflect upon his or her own existence. This is what Frost strives for in his poetry.

Some notes on theme and style: Frost often uses complex philosophical themes through his poetry. The three poem we read for the class are incredibly short, yet each line contains larger philosophic and social claims. Prof. Huang spent some time going over “The Road Not Taken,” reminding us that the poem is a lament for what could have been. Frost generally resorts to natural themes, moving from the city to the forest. Frost is writing during the early decades of the 20th century, a century marked by capitalism’s modernizing forces. Film was developing, photography and photo journalism were established as means of media communication, WWI (1914-1918) and WWII (1939-1945) ravished the global economy and mindset. Frost is writing in the midst of chaos and progress, trying to create a sense balance through poetry, a “momentary stay against confusion.” The poet is the one who is able to make life stop for a moment, a simple moment in which the reader can reflect upon his or her own existence. This is what Frost strives for in his poetry. In the poems that we have read the poetic narrator is always alone (or with an animal). No other human beings are around… why is that? If you could characterize Frost’s poetry using two or three themes, what would they be?

In the poems that we have read the poetic narrator is always alone (or with an animal). No other human beings are around… why is that? If you could characterize Frost’s poetry using two or three themes, what would they be? (1868- 1963)

(1868- 1963) nsciousness, bringing socio-political issues afflicting various communities into view. How do we see this belief enacted in the section entitled “Of the Sorrow Songs” which we read for the class? What does Du Bois say about language and music? How does music empower Du Bois?

nsciousness, bringing socio-political issues afflicting various communities into view. How do we see this belief enacted in the section entitled “Of the Sorrow Songs” which we read for the class? What does Du Bois say about language and music? How does music empower Du Bois?